New research led by Wolfson GBF quantifies how climate change will reshape global heating and cooling needs

Wolfson GBF Dr Jesus Lizana is the lead author of a new University of Oxford study assessing how heating and cooling needs are expected to change globally over the coming decades. Using Heating Degree Days (HDDs) and Cooling Degree Days (CDDs) – metrics commonly used in climate research and weather forecasting to estimate heating and cooling demand – the study assesses thermal exposure across three levels of global mean temperature rise above pre-industrial conditions: 1.0°C (2006–2016), 1.5°C, and 2.0°C, independent of the pathways leading to these global warming levels.

The findings, published in Nature Sustainability, have grave implications for humanity. The study shows that almost half the world’s population (3.79 billion) will be living with extreme heat by 2050 if the world reaches 2.0°C – a scenario that climate scientists see as increasingly likely. The largest affected populations are projected to be in India, Nigeria, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and the Philippines, the study predicts.

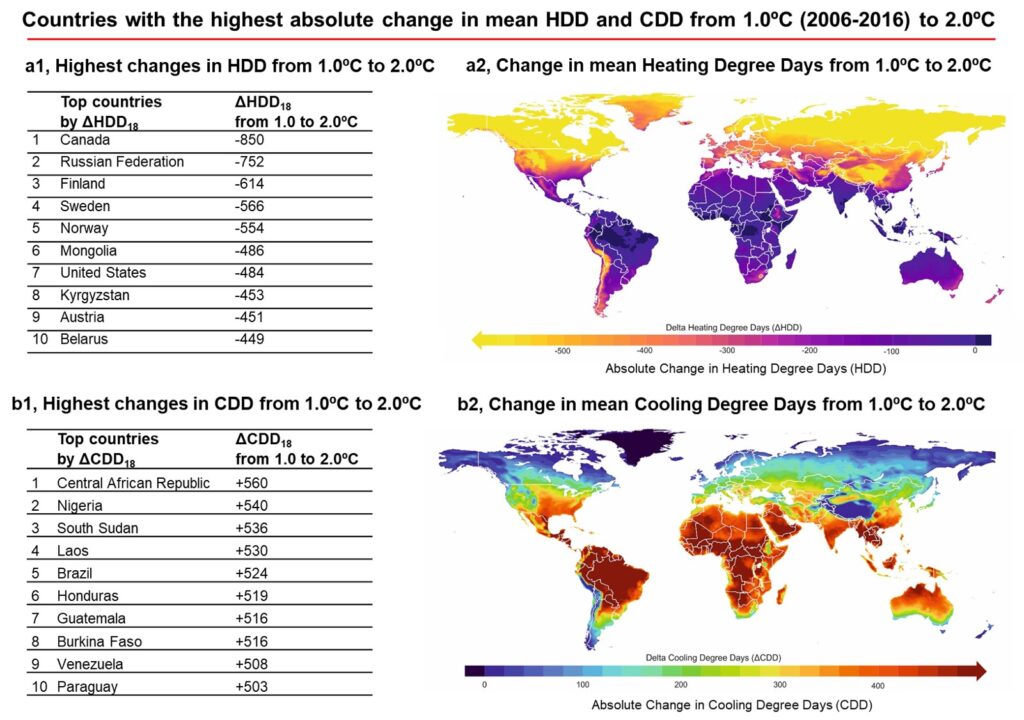

Most of the impacts are expected to emerge early, as the world passes the 1.5°C target set by the Paris Agreement, the authors warn. The Central African Republic, Nigeria, South Sudan, Laos, and Brazil are projected to experience the largest increases in dangerously hot conditions (Figure 1).

Countries with colder climates will see a much larger relative change in uncomfortably hot days, more than doubling in some cases. Compared with the 2006–2016 period, when the global mean temperature increase reached 1°C over pre-industrial levels, the study finds that warming to 2°C would lead to a doubling of heat exposure (100% increase) in Austria and Canada, 150% in the UK, Sweden, Finland, 200% in Norway, and a 230% increase in Ireland. Given that the built environment and infrastructure in these countries are predominantly designed for cold conditions (e.g. dwellings that maximise solar gains and minimise ventilation), even a moderate increase in temperature is likely to have disproportionately severe impacts compared with regions that have greater resources, adaptive capacity, and embodied capital to manage heat.

“Our study shows most of the changes in cooling and heating demand occur before reaching the 1.5ºC threshold, which will require significant adaptation measures to be implemented early on. For example, many homes may need air conditioning to be installed in the next five years, but temperatures will continue to rise long after that if we hit 2.0 of global warming,” says Dr Lizana, Associate Professor in Engineering Science and programme leader on zero-carbon heating and cooling at ZERO Institute. “To achieve the global goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, we must decarbonise the building sector while developing more effective and resilient adaptation strategies.”

“Our findings should be a wake-up call,” says Dr Radhika Khosla, Associate Professor at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment and leader of the Oxford Martin Future of Cooling Programme. “Overshooting 1.5°C of warming will have an unprecedented impact on everything from education and health to migration and farming. Net zero sustainable development remains the only established path to reversing this trend for ever hotter days. It is imperative politicians regain the initiative towards it.”

The projected increase in extreme heat will also lead to a significant rise in energy demand for cooling systems and corresponding emissions, while demand for heating in countries like Canada and Switzerland will decrease.

The authors employed the ‘HadAM4’ climate model developed by the UK’s Met Office – which can run on multiple personal computers of volunteers through climateprediction.net. “This computational efficiency enables the generation of very large, high-resolution climate projections across different global warming levels – from 1 °C (2006–2016) to 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C – independently of the timing of these changes,” explains Dr Lizana.

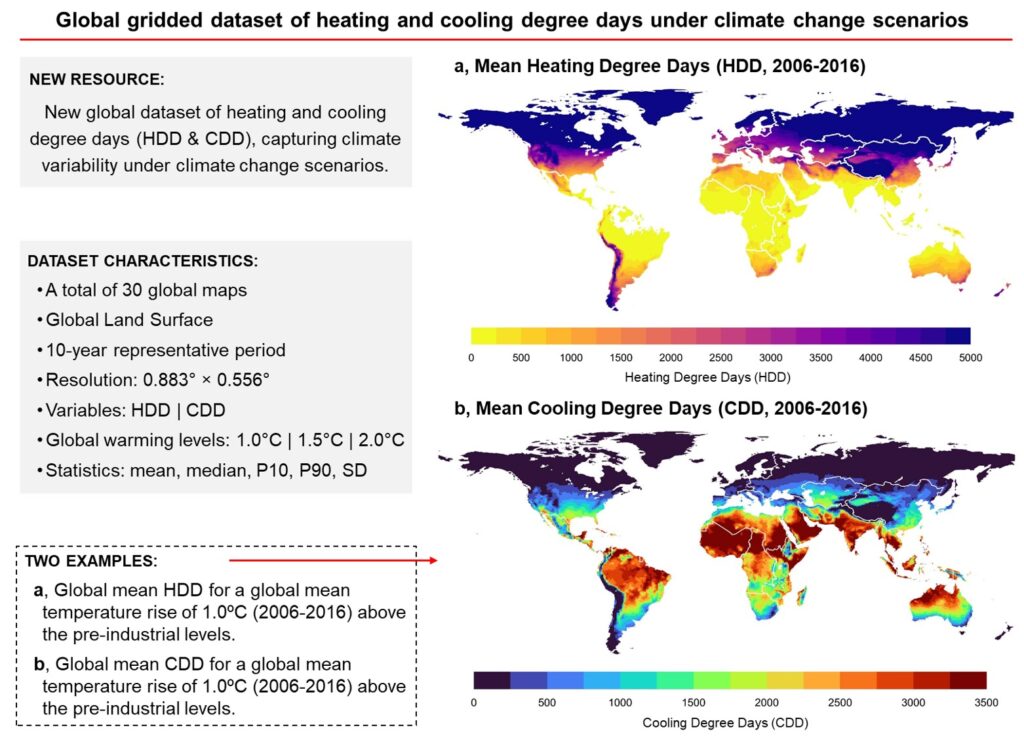

The study also includes an open-source dataset of global heating and cooling demand, comprising 30 global maps at ≈60km resolution that capture climate intensity in ‘cooling degree days’ and ‘heating degree days’ worldwide (Figure 2). This dataset provides a strong foundation for incorporating accessible climate data into sustainability planning and development policy.